Key Takeaways

- Technical metrics like accuracy, precision, and recall measure model behavior—not business value—and optimizing for the wrong metric can cost more than having no model at all

- The same metric value (like 15% precision) can be catastrophic in one context (credit underwriting) and revolutionary in another (marketing targeting), depending on error costs and baseline alternatives

- Stakeholder position determines metric priorities: loan originators need recall to maximize volume, loan buyers need precision to avoid bad paper, and regulators need explainability regardless of accuracy

Your data science team presents their new credit risk model with pride: 95% accuracy, F1 score of 0.87, and AUC of 0.92. The numbers look impressive. Your executive sponsor approves production deployment. Three months later, loan losses are up 40%, customer acquisition costs have spiked, and your compliance team is fielding fair lending complaints.

What went wrong? The model was technically excellent—but optimized for the wrong business objective.

This isn’t a hypothetical scenario. Research has shown that in many ML benchmarks, simple baseline models are competitive with complex architectures, while studies on predictive maintenance demonstrated that selecting models based on highest F1-score resulted in additional expenses rather than cost reduction.1 The fundamental problem: technical metrics measure model behavior while business metrics measure value creation. And the gap between them destroys more value than most organizations realize.

The Paradox of Precision: When 15% Is Both Disaster and Triumph

Consider precision—the percentage of positive predictions that are actually correct. A precision of 15% sounds terrible. And in credit underwriting, it would be: it means 85% of loan approvals will default, a catastrophic failure that would bankrupt most lenders within months. If you’re a portfolio lender holding credit risk, even 70% precision might be unacceptable depending on loss severity and recovery rates.

But now shift contexts to marketing. Your current email campaign converts at 10%. You build a model to predict purchase likelihood and target only high-probability buyers. The model achieves 15% precision—a 50% improvement over baseline. This isn’t just good; it’s transformational. Marketing spend efficiency jumps 50%, customer acquisition costs drop proportionally, and ROI on campaigns increases dramatically. The same metric, radically different business implications.

The difference lies in cost structures and baseline alternatives. Marketing campaigns face a different economic reality. After spending significantly to acquire leads, the marginal cost of outreach is minimal—sending emails costs fractions of a cent—while successful conversions generate hundreds or thousands in lifetime value. The optimization objective is lift over baseline: improving conversion from 10% to 15% means 50% more revenue from the same acquisition spend. False positives (targeting leads who won’t buy) cost almost nothing compared to false negatives (missing buyers who would have converted).

Credit underwriting operates in the opposite regime: high cost per failure (a defaulted loan loses principal plus collection costs) and asymmetric risk (one bad loan can erase profits from ten good ones). The optimization objective is absolute performance against a risk tolerance threshold, not relative improvement. False positives (approving loans that default) destroy capital. The business doesn’t care whether your model is better than the previous process—it cares whether default rates stay below profit margins.

This context-dependence applies to every classification metric. Accuracy sounds like the universal measure of model quality, but in fraud detection with 0.17% fraud rate, a model predicting “no fraud” for every transaction achieves 99.83% accuracy while catching zero fraud. Recall measures how many actual positive cases you catch—sounds good, right? But maximizing recall in cancer screening means flagging every suspicious result, flooding specialists with false alarms. When diagnostic capacity is limited, patients with real cancer wait longer for confirmation because the system is clogged with worried-well false positives. Accepting a few false negatives to maintain system function can paradoxically save more lives.

F1-score sounds like balance—the harmonic mean of precision and recall. But F1-score assumes equal cost for false positives and false negatives, which is rarely true. When fraud prevention researchers compared F1-optimized thresholds to business-cost-optimized thresholds, F1’s “balance” destroyed 6% of revenue.2

Your Position in the Value Chain Determines Your Metric Priorities

The most revealing test of whether you understand your ML problem is asking: “What does this stakeholder optimize for?” Different positions in the same value chain face fundamentally different business objectives, making one-size-fits-all metrics dangerous.

Take mortgage default prediction. Loan originators operating under an originate-to-distribute model prioritize recall because they make money from loan volume, not loan quality. Every approved loan generates origination fees regardless of whether it later defaults. Missing a creditworthy borrower (false negative) means lost revenue. Approving a borrower who later defaults (false positive) is the secondary market’s problem, not theirs—at least in the short term. A broker optimizing for quarterly revenue wants high recall (90%+ of good loans approved) even at the cost of lower precision, especially if enough loan buyers will purchase the paper despite quality concerns (though reputational concerns should reduce this incentive to a certain extent).

Portfolio lenders who retain credit risk face the opposite calculus. Banks holding loans on their balance sheet need precision for risk management and capital planning. They want accurate classification of default risk because they bear the losses. A false negative (declining a creditworthy borrower) means foregone interest income of perhaps $2,000 over the loan term. A false positive (approving a loan that defaults) means loss of $50,000 in principal plus collection costs. Consistent with Federal Reserve guidance on model risk management, banks retaining portfolio risk prioritize precision to minimize unexpected losses.3

Loan buyers and secondary market investors need precision for accurate pricing and portfolio construction. When purchasing mortgage-backed securities, investors calculate risk-adjusted returns based on predicted default rates. Overestimating credit quality (poor precision) means overpaying for risky assets, destroying portfolio returns. Institutional investors use market-determined credit spreads that require precise risk classification—not just rank-ordering loans as better or worse, but accurately predicting default probabilities within basis points.

Marketplace lenders like LendingClub operate two-sided platforms, creating split optimization problems. Borrowers want approval (high recall), while investors funding loans want accurate risk assessment (high precision). The business model requires balanced metrics that satisfy both stakeholder groups simultaneously.

Financial regulators represent another critical stakeholder with distinct priorities. For anti-money laundering models, regulatory guidance emphasizes comprehensive detection over operational efficiency, meaning recall matters far more than precision because missing potential money laundering creates severe legal and reputational consequences.5 Compliance officers face yet different metrics: model explainability for adverse action notices, disparate impact testing across demographic groups, and consistency of treatment regardless of whether it maximizes approval rates or portfolio returns.

In fraud detection, the stakeholder divide appears between operations teams and customer experience teams. Operations wants high recall to minimize fraud losses—catching 95%+ of fraudulent transactions even with significant false positive rates. But customer experience teams recognize that false positives (blocking legitimate transactions) create friction that drives customer churn. In 2016, Mastercard reported losses of $9 billion to fraud compared to $118 billion from false declines.6

The Business Reality: Metrics Are Meaningless Without Baseline Comparison

Even technically strong metrics become misleading without baseline comparison. Your model achieves 75% AUC—is that good? The answer depends entirely on what you’re comparing against.

For consumer credit scoring, AUC of 0.65-0.75 may be considered acceptable and 0.75+ is strong, but these are rough guidelines rather than standards. The critical question isn’t whether your model has high AUC, but whether it provides sufficient lift over current processes to justify development costs and operational risks.

The hierarchy of comparison reveals whether ML adds value:

- Naive baselines: Predicting the majority class (accuracy floor) or population default rate (AUC floor of 0.5) establishes whether the model learned anything at all

- Simple heuristics: Rule-based systems developed by domain experts represent the actual alternative if your ML project fails

- Current production models: Existing scorecards or manual processes define the bar for deployment—improvement must justify switching costs

- Theoretical limits: Irreducible error or Bayes error rate bounds what’s possible given available features

Research on predictive maintenance proved this hierarchy empirically. The model with highest F1-score produced higher maintenance costs than models selected using business cost functions, because F1-score optimizes for statistical balance while business optimization requires incorporating asymmetric error costs and maintenance scheduling constraints.1 The technically best model created the worst business outcomes.

In financial services, baseline comparison becomes even more critical because simple alternatives often perform surprisingly well. Credit bureau scores, despite limitations, achieve approximately 68-70% AUC with minimal implementation complexity.4 Before deploying complex neural networks requiring extensive feature engineering, real-time scoring infrastructure, and continuous retraining, you need to demonstrate material improvement over bureau scores—not just statistical significance but practical business value measured in loss rate reduction or approval rate increase at constant risk.

The Path Forward: Building Business-Aligned Evaluation Frameworks

The solution isn’t abandoning technical metrics—precision, recall, F1, and AUC remain essential for model development and debugging. The solution is bridging the gap between technical performance and business outcomes through explicit cost-benefit analysis.

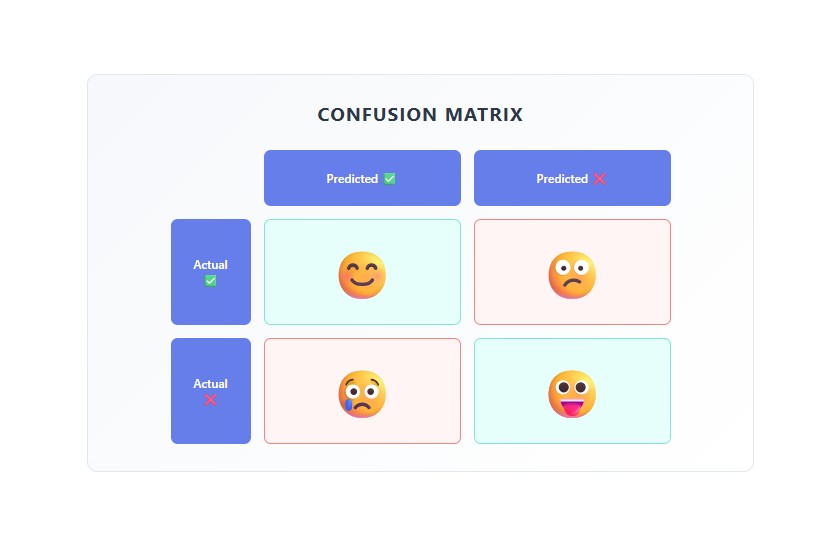

For classification problems, this means constructing cost matrices that monetize errors. For instance, consider the following business outcome matrix for a balance sheet lender:

Reality: Default Reality: No Default

Predict Default: $0 -$5,000 (lost opportunity)

Predict No Default: -$50,000 (loss) +$2,000 (interest earned)This immediately reveals why different stakeholders optimize differently. The originator’s matrix might show -$1,000 for false positives (lost origination fee) but only -$500 for false negatives (if they face limited repurchase risk), making recall optimization rational. The portfolio lender’s matrix shows the full -$50,000 loss, making precision essential.

The regulatory dimension adds a critical constraint: in financial services, some metrics matter for compliance regardless of business optimization. Fair lending laws require demonstrating that models don’t create disparate impact on protected classes, meaning consistency of outcomes across demographic groups becomes as important as overall accuracy. Different regulatory agencies have varying approaches to disparate impact analysis, with some federal and state agencies maintaining it as a compliance consideration even as supervisory emphasis has evolved.

The Strategic Imperative: Aligning ML Metrics With Business Reality

The organizations that extract value from machine learning aren’t those with the most sophisticated models—they’re those that align technical metrics with business objectives from project inception. This requires three disciplines:

First, translate business objectives into explicit cost functions before model development begins. “Reduce defaults” isn’t specific enough—is the goal minimizing loss rates (optimize precision), maximizing approval volume at constant risk (optimize recall at threshold), or improving rank-ordering for pricing? The answer determines feature selection, model architecture, and evaluation frameworks.

Second, validate metrics against stakeholder priorities through structured elicitation. Stakeholders often cannot articulate precise cost functions but can make comparative judgments between model outputs, allowing preferences to be inferred and translated into optimization objectives. Research on crowdsourced ML evaluation identified five distinct stakeholder clusters with different metric preferences in job-matching systems, concluding that “using predetermined metrics without soliciting stakeholder opinions leads to unfair disregard for stakeholders in the ML pipeline”.7

Third, measure business impact through controlled experiments rather than offline evaluation alone. The model that performs best on held-out test data may not perform best in production where data distribution shifts, user behavior responds to predictions, and operational constraints differ from training assumptions. A/B testing that compares ML-driven decisions against baseline processes remains a key measure of business value creation.

The compliance-versus-speed tension documented in financial services applies equally to ML deployment. Sometimes 70% precision that deploys this quarter beats 95% precision that takes 6 months—the competitor who ships faster captures market share while you optimize metrics. But deploying models that fail compliance review, create customer experience friction through excessive false positives, or optimize for the wrong stakeholder creates value destruction that no amount of technical sophistication can fix.

At Arrow Intelligent Consulting, we’re building ML systems that bridge this gap—delivering models that are technically sound, business-aligned, and operationally robust from day one.

References

-

Spiegel, S., Mueller, F., Weismann, D., & Bird, J. (2018). Cost-Sensitive Learning for Predictive Maintenance. arXiv:1809.10979. https://arxiv.org/abs/1809.10979. On baseline model performance, see research summarized at https://verifywise.ai/lexicon/baseline-model-performance noting that simple baselines are often competitive with complex ML architectures

-

Precision & Recall: When Conventional Fraud Metrics Fall Short. https://kount.com/blog/precision-recall-when-conventional-fraud-metrics-fall-short

-

Federal Reserve Supervisory Guidance on Model Risk Management, SR 11-7, 2011. https://www.federalreserve.gov/supervisionreg/srletters/sr1107.htm. General principles regarding model risk and financial loss applied to portfolio lending context

-

Berg, T., Burg, V., Gombović, A., & Puri, M. (2020). On the Rise of FinTechs: Credit Scoring Using Digital Footprints. The Review of Financial Studies, 33(7), 2845-2897. https://academic.oup.com/rfs/article/33/7/2845/5568311. Study shows digital footprint models match or slightly exceed credit bureau score performance

-

Federal Reserve, OCC, FDIC, NCUA, FinCEN Interagency Statement on Model Risk Management for Bank Systems Supporting Bank Secrecy Act/Anti-Money Laundering Compliance, SR 21-8, 2021. https://www.federalreserve.gov/supervisionreg/srletters/SR2108.htm. Guidance emphasizes comprehensive detection of potential illicit activity

-

Mastercard false decline statistics cited in NeuroID, “New Account Fraud Detection: Identify Genuine Customers,” https://www.neuro-id.com/resource/blog/new-account-fraud-detection-identify-genuine-customers/ (referencing FintechFutures, 2016)

-

Yokota, R., & Nakao, Y. (2025). Using predetermined metrics without soliciting stakeholder opinions is problematic because it leads to an unfair disregard for stakeholders in the ML pipeline. arXiv:2503.05796. https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.05796